By Robin Glover

The recovery process for a j-pouch is just that. It’s a process. It takes time and patience and is different for everyone. For some, it can be relatively easy. For others, it can be a winding path with twists and turns just like the colon that was removed for it.

But one thing is the same for practically everyone: j-pouch surgery offers hope for a return to a life that’s less encumbered by the alternatives. Seriously, who doesn’t want to poop out of their butt again if given the opportunity? Oh, and getting rid of that disease-ravaged large intestine is a plus, too.

What Is A J-Pouch?

In case you’re reading this to research information for yourself, friend or family member, here’s a quick explanation of what a j-pouch is:

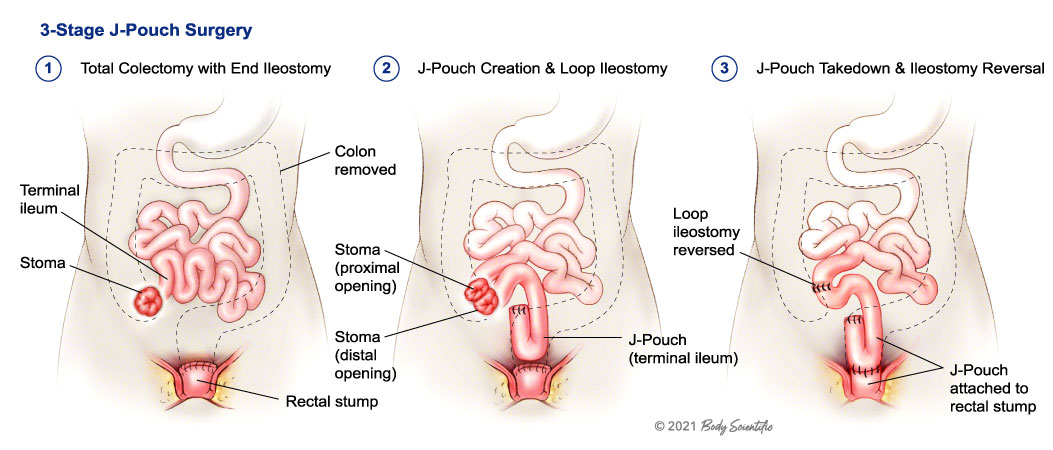

Medically known as Ileal Pouch Anal Anastomosis (IPAA) surgery, it involves removing the entire colon and rectum and then connecting the small intestine directly to the anus. The term j-pouch refers to the shape of the “pouch” that’s created when the surgeon folds the small intestine on itself and creates a reservoir to hold waste until it is passed through the anus. It can also be known as an s-pouch or w-pouch based on how it’s surgically constructed. J-Pouch surgery is most often done in cases of ulcerative colitis where there is no disease in the small intestine or as a result of FAP, colorectal cancer or a bowel perforation.

The surgery for a j-pouch almost always involves two or three steps. The first step, and usually the more major surgery, is to remove the large intestine. At the same time, an ileostomy is created that will be used until the small intestine is reattached. This will be a temporary external pouch.

Depending on individual circumstances, the first surgery can also involve removing the rectum and creating the internal j-pouch. However, it can also be its own separate procedure. But either way, the final step is to reverse the ileostomy and connect the small intestine to the anus. At this point, no external pouch is needed and the traditional route of passing stool can resume.

Be aware that the patient has the right to decide between a J-pouch or keeping the ostomy and should know not all temporary ostomies are able to be taken down and not all J-pouches are able to be connected.

Early Recovery From J-Pouch Surgery

It’s an exciting experience when you wake up from the final surgery and see that there’s no longer a need to have a pouch attached to you. What was once your stoma is now a still pretty nasty wound, but one that will heal and become just another proud scar.

another proud scar.

Things won’t be working quite yet though. It will be a few days before you actually have a bowel movement. Sometimes it can take longer, but that’s not a big deal. When you’re in the hospital you’ll be monitored and well taken care of. You likely won’t go home until your doctors are sure everything is working correctly, including being able to eat and pass solid food.

Everything that comes out will still be liquid, though. It will be a little bit before you start passing anything even semi-solid. And you might not ever get to that point or only have it happen on rare occasions. There’s nothing unusual about that.

Diet Right After Going Home

The diet you follow after getting home from the hospital will be communicated to you by your doctor and you’ll probably go home with many guides and resources. Mainly, staying hydrated is very important and avoid raw fruits or vegetables, nuts, whole grain, seeds, or anything else that doesn’t digest in around two hours. Since you no longer have a large intestine, food has much less time to be processed and if you eat a handful of nuts they’re going to come out the same way they went down.

Check the Eating with an Ostomy Guide for a much more complete diet guideline.

But, even worse, it can cause a blockage. Blockages are the bane of a j-pouch’s existence. You need to be careful about what you eat (typically called a “low residue” diet) and chew your food thoroughly. Chew extra. And then some more. Take small bites and don’t take any risks right away. Introduce new foods slowly.

NOTE: Your doctor or dietician will know the best foods to eat and what to avoid for your specific needs. Always follow their directions before anything you read on the internet.

Getting To Know Your J-Pouch

It can take a while after surgery to completely adjust to your new plumbing. You’ll learn what foods are “safe foods” and which to avoid. You’ll also learn about how your j-pouch behaves and how it affects your daily life.

For example, you’ll start to get an idea of how many times per day you’ll go to the bathroom and what consistency you can expect. You’ll also learn what each sense of urgency means and when you need to go to the bathroom right away and when you can hold it. It will feel like you need to go to the bathroom a lot and you’ll probably actually need to at the beginning. But, over time, your j-pouch will stretch and grow to be able to hold more before needing to be emptied.

Ideally, after everything settles down, you will only go to the bathroom 4 to 8 times a day and it will be a simple and quick emptying process.

You’ll Experience Butt Burn

Speaking of going to the bathroom a lot, you may experience what is known as “butt burn.” This is because, on top of going to the bathroom more often, without a large intestine your stool will be much more acidic from digestive enzymes.

from digestive enzymes.

It’s necessary to take special care and make sure everything is extra clean. A bidet is a great idea because rubbing with toilet paper can also cause irritation. There are also many creams and lotions you can use to soothe and protect. Zinc-based lotions are a good place to start. And get some disposable gloves while you’re at it.

You may go to the bathroom up to 20 times a day (or more) and experience irritation from going so much. But, it will get better as you learn more about your j-pouch and develop processes that work best for you. In the end (no pun intended), you’ll get to a point where you’re comfortable and know how to manage it like an expert.

Ideally, after everything settles down, you will only go to the bathroom 4 to 8 times a day and it will be a simple and quick emptying process.

It’s Not Always Easy

As mentioned, j-pouch recovery is a process. At the beginning, there will be accidents (typically nighttime) and discomfort. It’s a whole new way of digesting food and your body needs time to adjust. And you will need time to adjust to it too. It’s a major change.

Be aware of possible complications such as pouchitis and tell your doctor if you have more frequent or blood in your bowel movements.If you have a j-pouch or need one, you’ve already been through a lot. You know you’re resilient and can make it through almost anything. This is just another step in your journey.

Don’t let any of this discourage you. There’s a reason you decided to get a j-pouch and there’s a wealth of resources and support out there to help. Everything you will experience has been experienced before and the j-pouch community is always ready to help. But keep in mind that social media is often a place to vent so you might see more negative than positive posts.

So focus on the good, be patient, and look forward to enjoying pooping out of your butt again!

Robin Glover is a writer based in the Houston area. He has a permanent ostomy after being diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease in 2017.