Twenty-seven feet. That’s the length of a typical intestinal tract.

Twenty-seven inches…that’s all I have left of MY intestines.

But I didn’t lose more than 90 percent of my intestines all at once. My journey to a Short Bowel Syndrome (SBS) diagnosis is a long story, but one that I hope will help others feel less alone.

| If you are living with Short Bowel Syndrome and rely on parenteral support, there’s an SBS Mentor available to connect with you. Click here to learn more. |

My Story Begins

I was diagnosed with Crohn’s in my early teens. I was 23 when I had my first bowel resection and ileostomy. Over the next 35 years or so, a pattern developed: from Thanksgiving until Easter, I would become increasingly sick. For me that meant more Crohn’s-related pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and bleeding. I relied on my family, friends, and my doctors to help me manage through those tough times. I was able to graduate college Phi Beta Kappa, summa cum laude, earn a master’s degree in immunology, and become another of the many scientists in my family. But each year, I felt worse, and the symptoms lasted longer until, finally, I would need additional surgery to remove more diseased intestines. Before each operation, my surgeons would tell me they would need to remove just the minimum amount so I would not develop “Short Bowel Syndrome” or “SBS”. I didn’t understand their concerns. I kept thinking, “If they can remove all the bad parts and I end up with SBS, what’s the big deal? I’m already living with all these intestinal problems; it couldn’t be worse.” Or could it??

It got to the point where surgery was just buying me time. And it wasn’t quality time. I can’t even count how often my husband got up in the middle of the night to take me to the ER, and the hours he spent there with me. I had to stop working and go on disability. Added to the pain, diarrhea, and vomiting were more frequent bowel obstructions and fistulas. In my case, the fistulas could not be controlled or repaired. I needed major surgery to remove all the bits and pieces of reconnected intestines that were kinked, strictured and sticking, and patch up the areas where the fistulas had formed.

Major Surgery and an SBS Diagnosis

I had that surgery in August 2013 and had never been more terrified. A few days later, I was moved from the ICU to the “progressive care unit.” The image is still burned in my memory, my husband standing next to me. My surgeon stood in front of me and said, “You definitely have Short Bowel Syndrome now.” He gestured—held his hands in front of himself a bit more than hip-width apart. I thought he was just making a random gesture. “68 centimeters,” he said. That came to a little more than two feet.

I understood the part about my intestines being “shorter” but I didn’t yet understand that there was more to my SBS than just the length of my remaining intestines. I also had reduced function of my remaining intestines, meaning I wasn’t able to absorb enough nutrients from food and drink and needed to depend on parenteral support to maintain my health. This is sometimes referred to as SBS with intestinal failure, or “SBS-IF”.

I was not at all prepared for life with SBS. I was now receiving parenteral support (PS) in the form of two liters of IV hydration twice a week with magnesium and anti-diarrheal drugs. I was experiencing life-threatening electrolyte and mineral imbalances. Knowing I could die within hours if I couldn’t get adequately hydrated and get my electrolytes balanced was the most frightening thing to me. In fact, not two months after my surgery, I became so severely dehydrated that by the time I got to the ER my kidneys had shut down, and my potassium was so high I was on the verge of cardiac arrest. When I was able to sleep, I kept my fingers on my pulse. I was used to always looking for the nearest bathroom. Now, I was also looking for the nearest ER.

Partnering with my Doctor to Start SBS Treatment

There came a day when I finally cried with my doctor. He made some phone calls to colleagues to find out what they were doing to treat their SBS patients. On Christmas Eve, he called me excitedly to say he had learned that GATTEX® (teduglutide) for subcutaneous injection is a prescription medicine used in adults and children aged 1 year and older with Short Bowel Syndrome who need additional nutrition or fluids from intravenous (IV) feeding (parenteral support). We talked and, as part of that conversation, he encouraged me to read more about the possible benefits and serious risks, including making abnormal cells grow faster, polyps in the intestines, blockage of the bowel (intestines), swelling (inflammation) or blockage of your gallbladder or pancreas, and fluid overload.

Please continue reading for additional Important Safety Information.

After continuing to talk with my doctor about the possible side effects, I decided I would try it. A Takeda Patient Support nurse came to my home to show me how to prepare and measure my dose and give my GATTEX injection correctly. We practiced injecting on a dummy device. And then it was time to do the real thing. I remember how nervous I was, but what a feeling to be able to do this for myself!

Now, I take my GATTEX at night, right before bedtime. I rotate between four different injection sites on my body. I number the vials in my kit “1, 2, 3, 4” to remind me which spot to inject on which day. Under the supervision of my infusion nurse and my doctor, I was able to reduce my IV hydration from routinely getting two liters twice a week to regularly getting one liter once a week and, for a time, only receiving IV hydration on an as-needed basis. While this was true for me, not all people who take GATTEX will be able to reduce their weekly PS volume. I eventually had to start PS again. I do sometimes experience redness after injecting or notice a bloated feeling, and I have experienced some bowel blockages. I worked with my doctor to manage these side effects. He temporarily stopped GATTEX when I developed each bowel blockage and restarted GATTEX when they resolved. Again, this is my experience, and others may have different experiences with the medication.

I am glad I have a team of doctors I can trust, and who listen to me. I believe it’s important to educate yourself about treatment options, including the risks and benefits, and to communicate with your doctors when something isn’t working. My doctors continue to closely monitor me and adjust my medications, including all my electrolytes, minerals, and oral supplements. Overall, I am happy with my results.

I have learned many lessons through my life with serious illness, but I think one of the most important things I’ve learned is to be flexible. For me, this means being honest with myself and what I am physically capable of doing in a given day—to recognize that what I can do today might be different from what I could to do the day before. Nowadays, I try not to push myself beyond my limits.

And there’s one more thing I’m doing for myself: I’m sharing my experiences with others. For so long, I was not involved with the Short Bowel Syndrome community. Friends and family are wonderful, but I think it’s important to find a network of people who have been through similar experiences. For me, the people who truly understand what I’ve been through have helped me come out from the shadows, and I am happy with who I am.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

What is the most important information I should know about GATTEX? GATTEX may cause serious side effects, including:

Making abnormal cells grow faster

GATTEX can make abnormal cells that are already in your body grow faster. There is an increased risk that abnormal cells could become cancer. If you get cancer of the bowel (intestines), liver, gallbladder or pancreas while using GATTEX, your healthcare provider should stop GATTEX. If you get other types of cancers, you and your healthcare provider should discuss the risks and benefits of using GATTEX.

Polyps in the intestines

Polyps are growths on the inside of the intestines. For adult patients, your healthcare provider will have your colon and upper intestines checked for polyps within 6 months before starting GATTEX, and have any polyps removed. To keep using GATTEX, your healthcare provider should have your colon and upper intestines checked for polyps at the end of 1 year of using GATTEX.

For pediatric patients, your healthcare provider will check for blood in the stool within 6 months before starting GATTEX. If there is blood in the stool, your healthcare provider will check your colon and upper intestines for polyps, and have any polyps removed. To keep using GATTEX, your healthcare provider will check for blood in the stool every year during treatment of GATTEX. If there is blood in the stool, your healthcare provider will check your colon and upper intestines for polyps. The colon will be checked for polyps at the end of 1 year of using GATTEX.

For adult and pediatric patients, if no polyp is found at the end of 1 year, your healthcare provider should check you for polyps as needed and at least every 5 years. If any new polyps are found, your healthcare provider will have them removed and may recommend additional monitoring. If cancer is found in a polyp, your healthcare provider should stop GATTEX.

Blockage of the bowel (intestines)

A bowel blockage keeps food, fluids, and gas from moving through the bowels in the normal way. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you have any of these symptoms of a bowel or stomal blockage:

- trouble having a bowel movement or passing gas

- stomach area (abdomen) pain or swelling

- nausea

- vomiting

- swelling and blockage of your stoma opening, if you have a stoma

If a blockage is found, your healthcare provider may temporarily stop GATTEX.

Swelling (inflammation) or blockage of your gallbladder or pancreas

Your healthcare provider will do tests to check your gallbladder and pancreas within 6 months before starting GATTEX and at least every 6 months while you are using GATTEX. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you get:

- stomach area (abdomen) pain and tenderness

- chills

- fever

- a change in your stools

- nausea

- vomiting

- dark urine

- yellowing of your skin or the whites of your eyes

Fluid overload

Your healthcare provider will check you for too much fluid in your body. Too much fluid in your body may lead to heart failure, especially if you have heart problems. Tell your healthcare provider if you get swelling in your feet and ankles, you gain weight very quickly (water weight), or you have trouble breathing.

The most common side effects of GATTEX include:

- stomach area (abdomen) pain or swelling

- nausea

- cold or flu symptoms

- skin reaction where the injection was given

- vomiting

- swelling of the hands or feet

- allergic reactions

The side effects of GATTEX in children and adolescents are similar to those seen in adults. Tell your healthcare provider if you have any side effect that bothers you or that does not go away.

What should I tell my healthcare provider before using GATTEX?

Tell your healthcare provider about all your medical conditions, including if you or your child:

- have cancer or a history of cancer

- have or had polyps anywhere in your bowel (intestines) or rectum

- have heart problems

- have high blood pressure

- have problems with your gallbladder, pancreas, kidneys

- are pregnant or planning to become It is not known if GATTEX will harm your unborn baby. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you become pregnant while using GATTEX.

- are breastfeeding or plan to It is not known if GATTEX passes into your breast milk. You should not breastfeed during treatment with GATTEX. Talk to your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby while using GATTEX.

Tell your healthcare providers about all the medicines you take, including prescription or over-the counter medicines, vitamins, and herbal supplements. Using GATTEX with certain other medicines may affect each other causing side effects. Your other healthcare providers may need to change the dose of any oral medicines (medicines taken by mouth) you take while using GATTEX. Tell the healthcare provider who gives you GATTEX if you will be taking a new oral medicine.

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You are encouraged to report negative side effects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit www.fda.gov/medwatch or call 1-800-FDA-1088.

What is GATTEX®?

GATTEX® (teduglutide) for subcutaneous injection is a prescription medicine used in adults and children 1 year of age and older with Short Bowel Syndrome (SBS) who need additional nutrition or fluids from intravenous (IV) feeding (parenteral support). It is not known if GATTEX is safe and effective in children under 1 year of age.

For additional safety information, click here for full Prescribing Information and Medication Guide, and discuss any questions with your doctor.

Editor’s Note: This educational article is from one of our digital sponsors, Takeda. Sponsor support along with donations from our readers like you help to maintain our website and the free trusted resources of UOAA, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

GATTEX and the GATTEX Logo are registered trademarks of Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc. TAKEDA and the TAKEDA Logo are registered trademarks of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. ©2024 Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc. All rights reserved. 1-877-TAKEDA-7 (1-877-825-3327). US-TED-1399v3.0 10/24

Adapting Activities

Adapting Activities

I started to panic with every procedure, wondering if everything would go routinely or if we would be surprised with unexpected problems.

I started to panic with every procedure, wondering if everything would go routinely or if we would be surprised with unexpected problems.

sleeping. I couldn’t stand a lot of smells or people- so not much socializing.

sleeping. I couldn’t stand a lot of smells or people- so not much socializing.  that you had to find through a scavenger hunt.

that you had to find through a scavenger hunt.

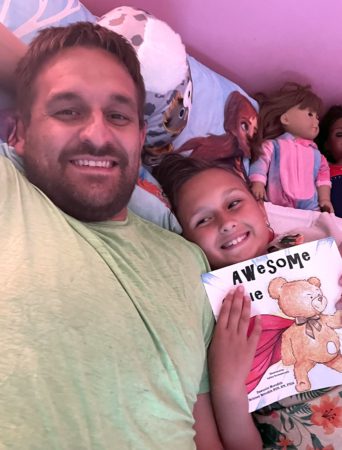

way that is taboo or sometimes uncomfortable to discuss. In a world where it is easy to stay isolated and afraid of connection, I have found some of my closest companions were waiting for the same opportunity; hiding away behind their shields of invisibility.

way that is taboo or sometimes uncomfortable to discuss. In a world where it is easy to stay isolated and afraid of connection, I have found some of my closest companions were waiting for the same opportunity; hiding away behind their shields of invisibility.